Previous blog in this series: Guide for Zero-Trust Conditional Access design – Part 0: how to document? – The Entra Guy

A lot of examples for conditional access design start from the premise “given this set of conditions, how can I make sure that security controls X & Y are enforced”?

For example: “If our users are not working on-premise, they must authenticate using MFA”

But, what happens if your users are working on-premise? No rule applies? Or what happens with guest users? Or this group of external consultants that come in with their own device that you’ll need to add as an exception? Etc., etc.…

What is notably missing in conditional access, is the concept of a “catch all” rule.

This is however inherent to the way Conditional Access is designed to work: all rules that match the given set of conditions in which a user authenticates, will apply to the log-in session and the set of CA-Grant-controls will be combined. Hence, if there is no rule that applies to the set of conditions at a given sign-in situation, then there is no Grant-control; which implies: no restrictions!

You can reasonably argue that Microsoft could have adopted a zero-trust principle from the beginning: no CA rule applies? No access! However, historically, conditional access has been added to Azure AD after O365 and Azure were already in place at many customers and it took a few years to become fully mature.

So, how do you start with a zero-trust design?

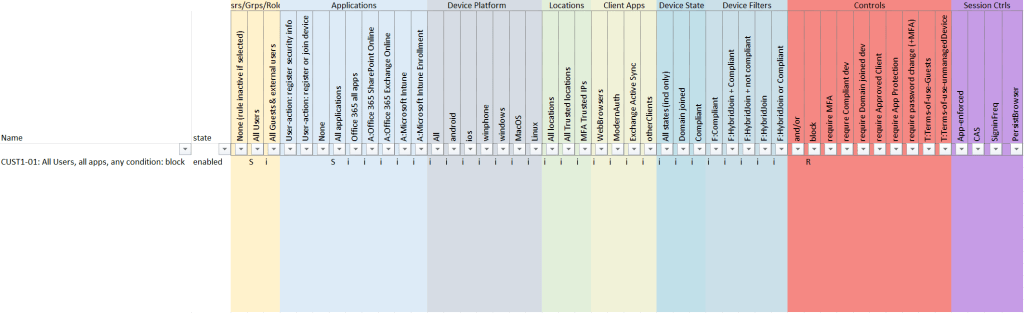

(to understand this way of documenting CA, please read “part 0” of my series)

If you would implement the rule above (DON’T DO THAT, please), you have essentially created the cloud-equivalent of putting a computer in a block of concrete and let it sink to the bottom of the Mariana Trench: completely secure, but you have a completely useless M365 tenant … only thing you can do now is call Microsoft Support and go through the struggle of gaining access to your tenant again …

So, one of the first rules you want to add in order to ensure you will never be blocked by your own mistakes when creating CA rules, is to add the “breakglass account”: an account with global admin privileges that is always exempted from any CA rule, MFA requirements, etc., and is hence only protected with a very strong (!) password. More info on Break-glass account(s) (a.k.a. Emergency Access Accounts) can be found here: Manage emergency access admin accounts – Microsoft Entra | Microsoft Learn

Any user that is member of this group, will be excluded from your CA rule(s) and will be able to login. So, make sure to have at least one global-admin in this group. Best-practice dictates that this global admin should never be used, except in the rare situation that you are fully blocked otherwise!

Good, we are now sure we don’t lock ourselves out … what’s next?

From now on, you will need to follow this simple rule: for every exception you make in a rule, you must create a new rule specifically for this exception.

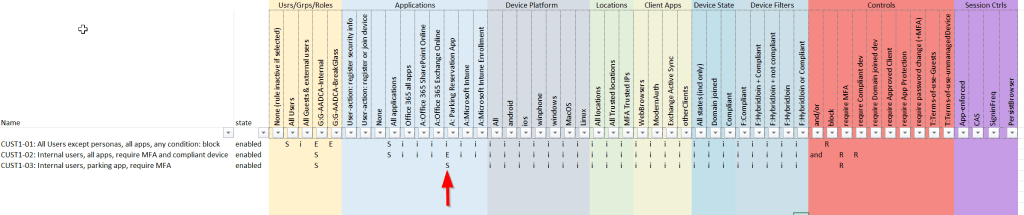

So, if we want to make sure now that our internal users can access all applications, but only after authentication with MFA and from a managed device, we need to update the rules as follows:

- We add the “G-AADCA Internal” group (which contains all accounts of internal users) as an exception to the first rule and

- add a new rule specifically for this group that requires MFA and compliant device in the grant-controls

So, now your internal users can access any app, provided they login from a compliant device and have completed MFA authentication.

Let’s take this a step further

Suppose that for your internal users, you want to make an exception that they are allowed to access the “parking reservation app” from any device (even if non-compliant), but are still required to authenticate with MFA, how do you do that?

- add the “Parking Reservation app” as an exception to the previous rule

- create a new rule that applies to “G-AADCA Internal” group and to the “Parking Reservation app” that requires MFA.

(note: why not add an exemption for this app to the first rule “CUST1-01”? well, in that case it would apply to ALL users, not only to the internal users group)

So, what is the advantage of this design approach?

- You are sure at all times that there is no combination of conditions for which there is no rule at all (except for the breakglass accounts, which is of course intended).

- Any new situation that is not specifically captured in CA rules, is still secure

- If you add a new user to the tenant, but you forgot to add him to the “G-AADCA-Internal” group, the user will be blocked (until added)

- If you add new applications, they will be covered by the existing CA rules, unless a specific rule is created for those apps.

Why is this now a “Zero-trust” design?

Well, you can argue about the semantics, but from my point of view, it does match the principles of zero-trust:

- Verify explicitly: any situation will be matched against a CA rule; there is no set of conditions that isn’t matched

- Least-privilege: if a user is not explicitly added to a conditional access group, he will be blocked! In many other designs that I have seen, new users are sometimes left out of CA rules until they have been added to a group, which implies: no restrictions!

- Assume breach: again, by ensuring that any condition is captured when users log in to the tenant, you can ensure that there are always multiple factors that are verified … if a hacker manages to successfully “phish” any user’s password, he will still be blocked

In the next parts of this series, I will dive a bit further in an overall design approach, based on devices, persona’s, and more…

Leave a comment